Andrea* walks into the pharmacy sporting casual clothes and sneakers, a purse slung over her shoulder. Small jewellery studs dot her face, and her warm, friendly face is framed by a short bob.

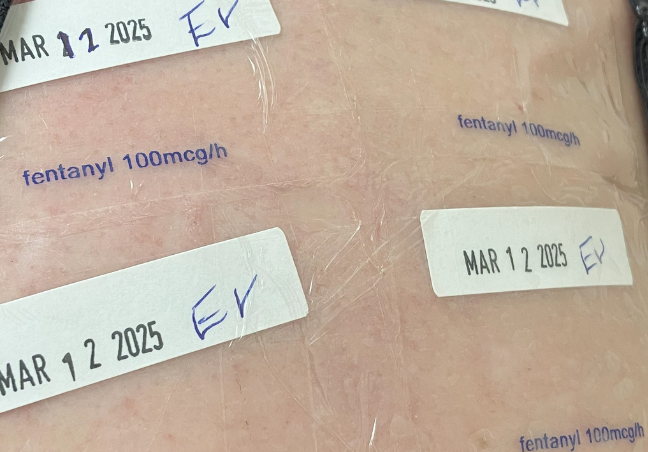

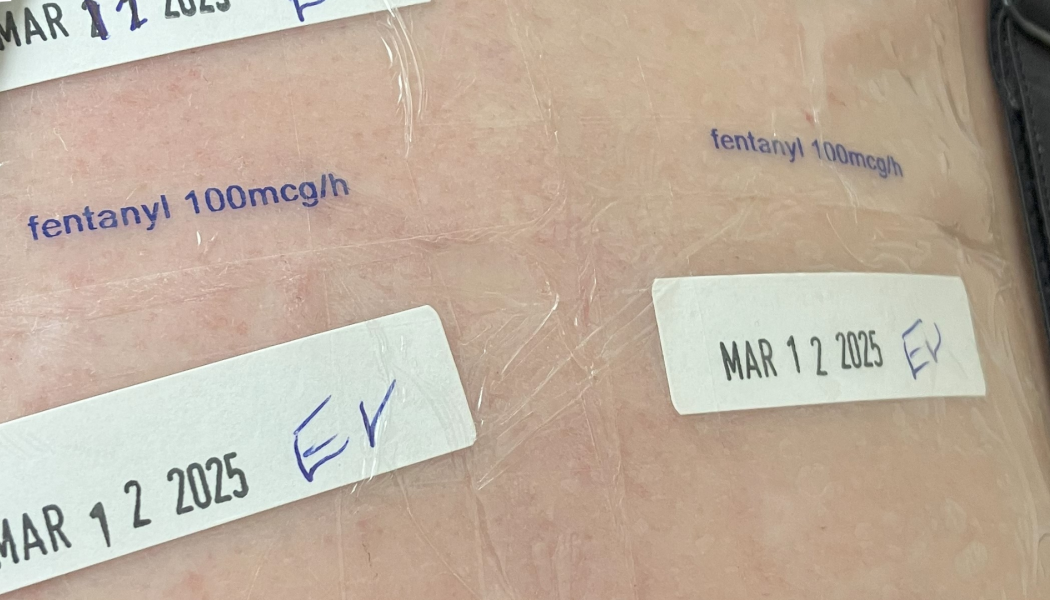

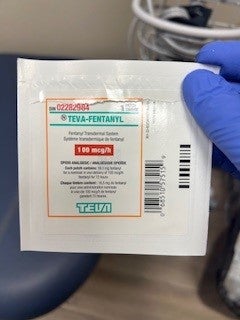

For the past two years, Andrea has been coming to this pharmacy two to three times a week to have her fentanyl patches changed by a registered nurse. Since she started the fentanyl patch program—under a broader program known as prescribed safer supply—she’s gone from living in a tent city in Kelowna to full-time employment, owning a car and renting a place of her own.

*Name changed to protect client's privacy and identity.