Content warning: This story deals with abuse, substance use and suicide.

Trauma has long been recognized as a powerful force that can shape a person’s life, impacting not just their emotional and psychological health, but physical well-being as well.

When trauma happens, especially early in life, it has the potential to change how the brain develops. It can disrupt our body’s ability to regulate stress hormones and affect key areas of the brain that control our emotions and behaviours.

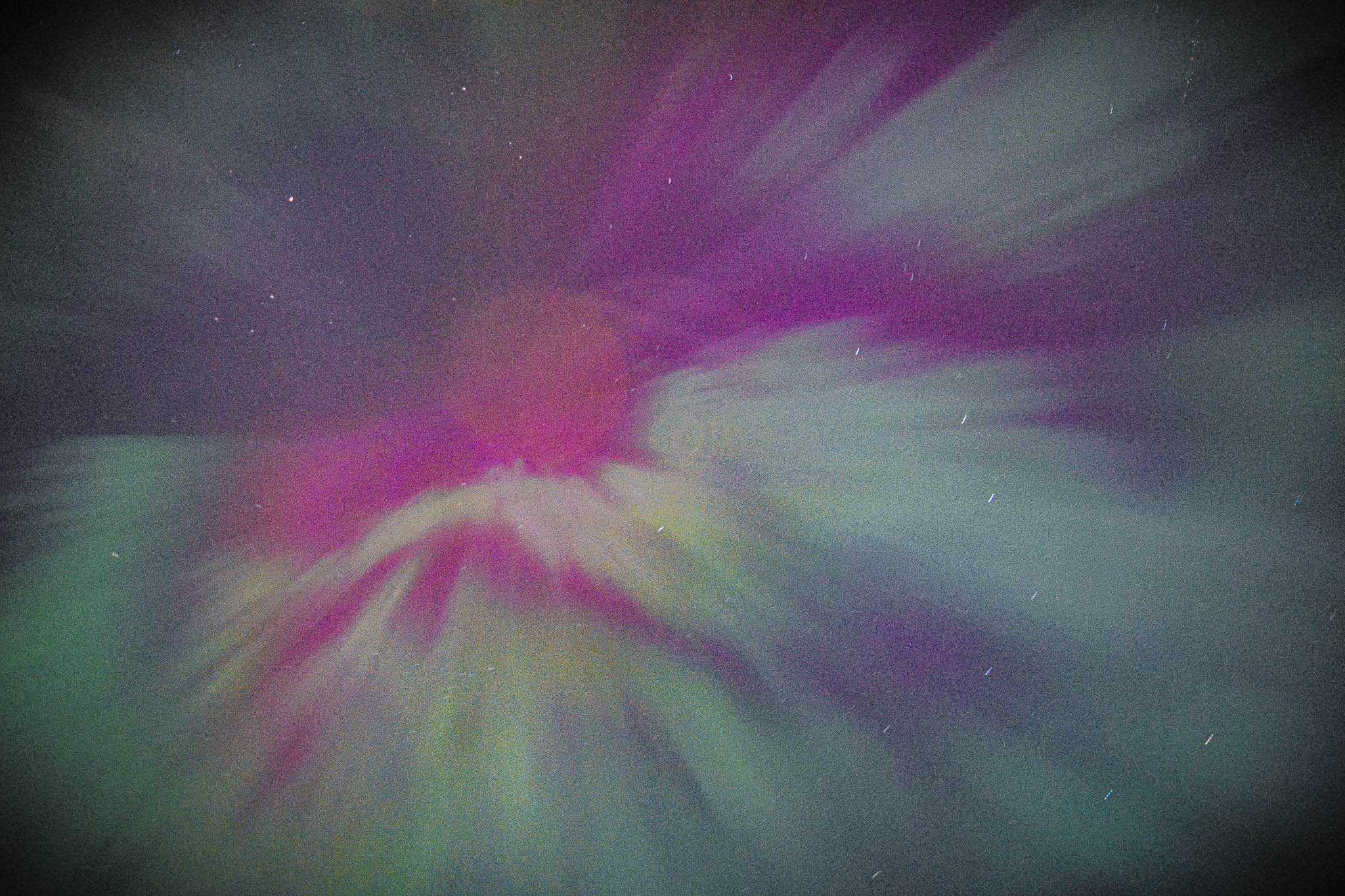

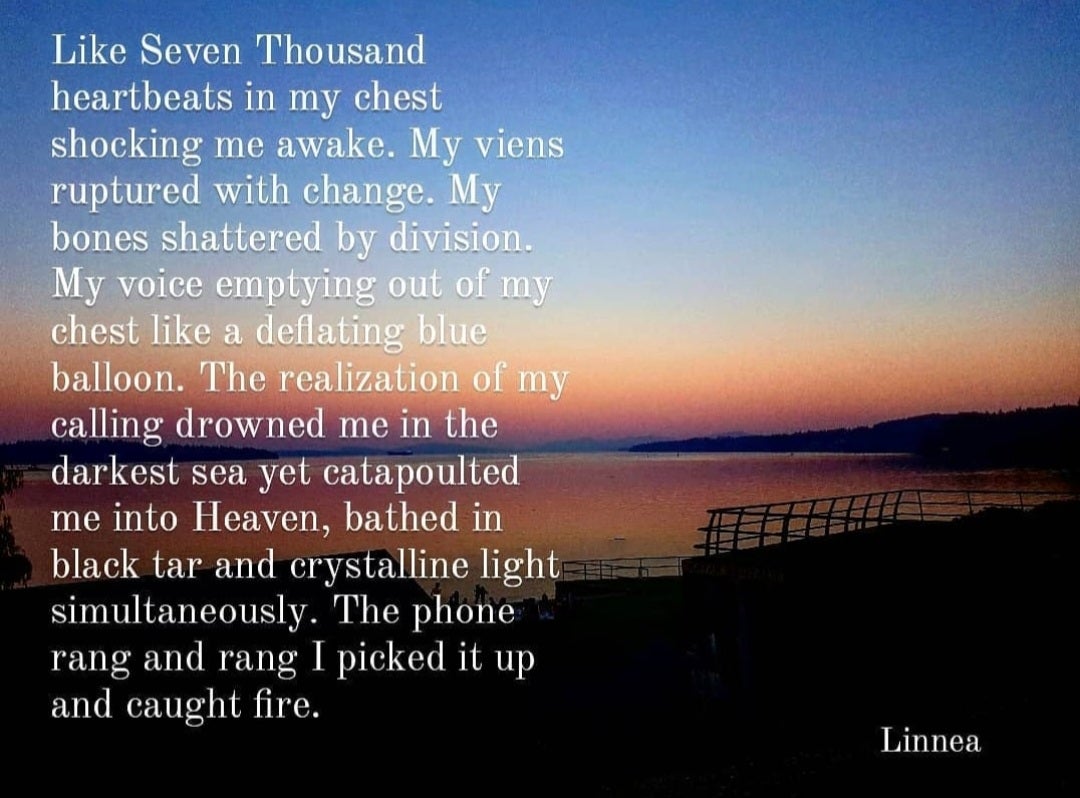

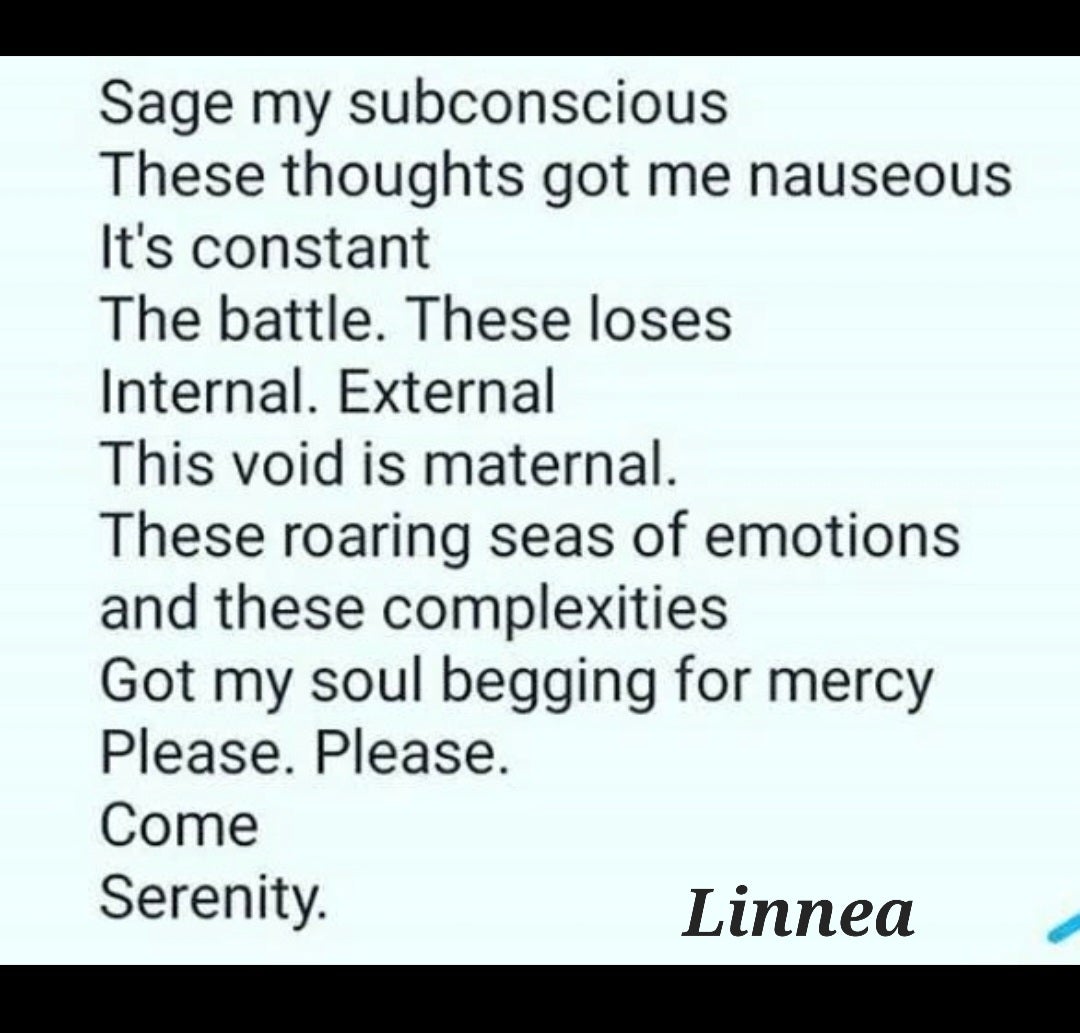

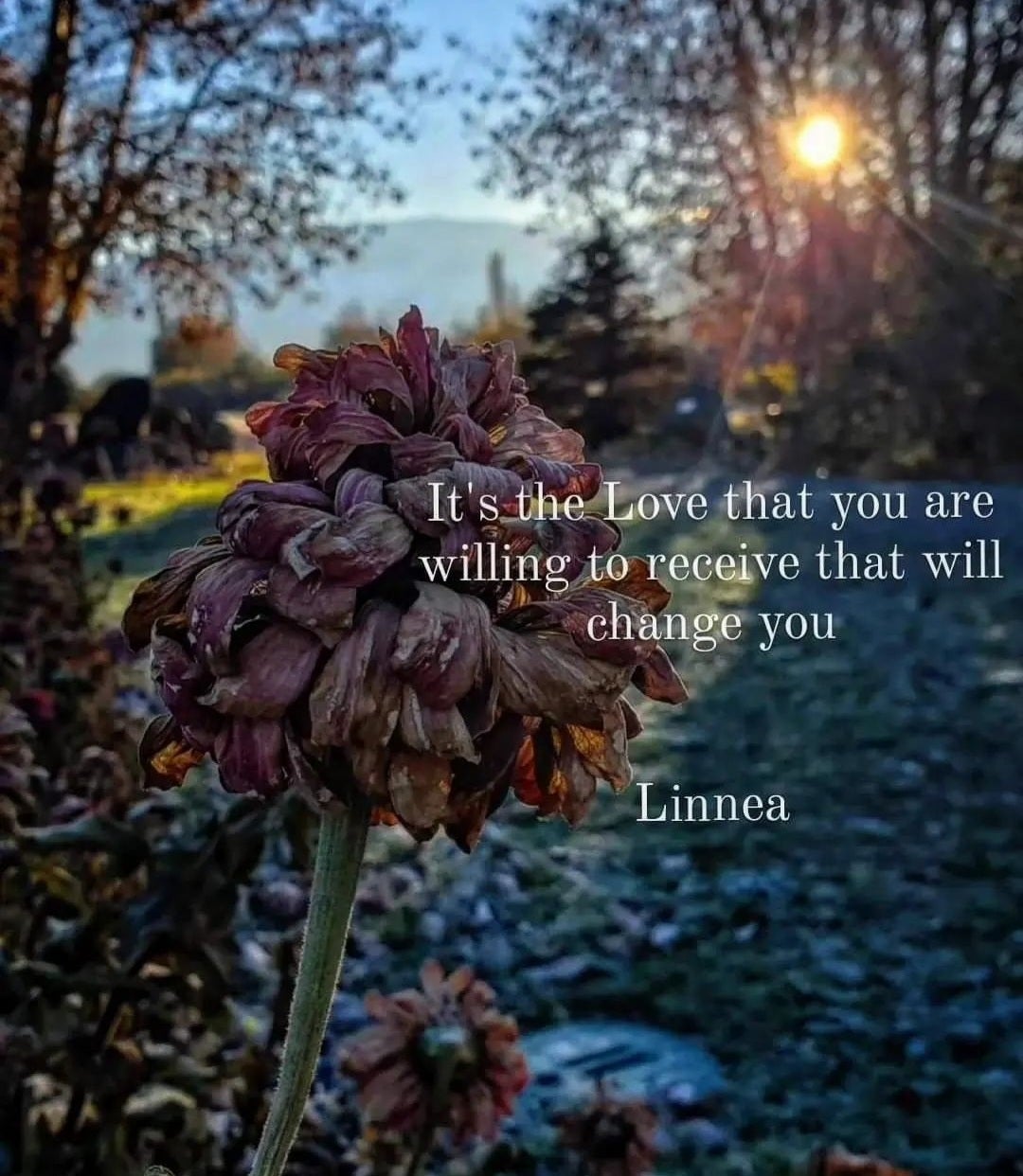

In this story, learn about trauma and its effects on our brains, nervous system and peoples' lives. You'll also hear from Linnea, a Peer Volunteer with Interior Health. Linnea shares her story of trauma and substance use, displayed as quotes throughout the story. We also share some of her poetry and photography that she posts on Instagram.